Origins and Purpose of the Martellos

Soon after the renewal of Britains' war with France in the spring of 1803, Captain William Ford, one of the military engineers working on the British defences in Kent, put forward a proposal for a chain of square gun-towers - `towers as sea fortresses' - along the coasts of Kent and Sussex. These were to be sited at close intervals, so that their fire crossed for mutual protection, while the high cost of their construction compared to existing field-works was to be partly offset by their lower maintenance requirements. After some eighteen months of debate inside and outside the military establishment, Ford's proposals were adopted in modified form and the round towers then constructed became known as Martellos.

Circular fortified towers, used as strongholds or look-outs, had been built from prehistoric times, but in northern Europe, they had fallen from favour late in the fifteenth century after the invention of gunpowder and artillery had led to radical changes in the design of fortifications. Around the Mediterranean however, where piracy remained a problem long after it had been eliminated in northern waters, stone towers capable of limited defence continued to be built on the coasts where they also acted as look-outs and places of refuge. Nearer home, military engineers had recognised the defensive possibilities of such towers when they had constructed a number on the coasts of Jersey and Guernsey in the 1780s, while in 1796 a circular gun-tower was built at Simons Bay in Cape Colony, now part of South Africa. Three larger towers were erected at Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1796-98 to protect British naval installations.

All these towers, although principally designed and sited to withstand ship-mounted assaults, differed markedly in design and capabilities from the towers soon to be built in south-east England.

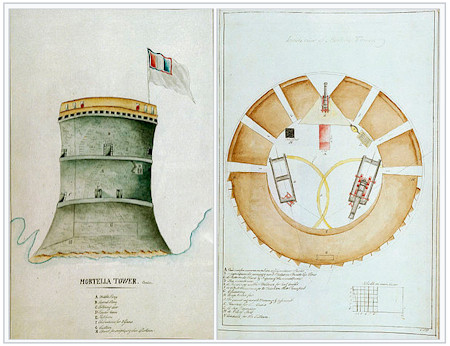

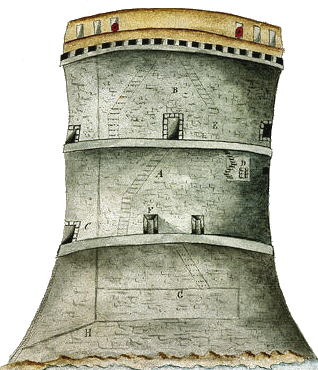

The strength of such towers had been dramatically demonstrated to the British in February 1794, when a fleet under Lord Hood had been sent to capture Corsica. Crucial to the British attack was the capture of a stone watch-tower on Mortella Point. This tower was armed with one 6-pounder and two 18-pounder guns by the French and it successfully repulsed an attack by HMS Fortitude (74 guns) and HMS Juno (32 guns), both of which withdrew with serious damage and some sixty casualties. The army then built a four-gun battery some 150 yards from the tower and after two days of continuous bombardment forced the garrison to surrender.

Not surprisingly, the resistance of this tower made a deep impression on the attackers; drawings and sketches were made of it, and before its demolition prior to the British withdrawal from Corsica in the autumn of 1796, a scale model was constructed for display in the Royal Artillery Museum at Woolwich.

Mortella Tower - Plan & Elevation Find out more

No doubt mindful of the strength of the Mortella tower, the British repaired and augmented by fifteen a chain of similar towers in 1798 when they re-occupied Minorca for the third time in the eighteenth century.

It is clear that these Mediterranean towers excited the attention of English military engineers of the day. For generations, they had been schooled to dismiss the defensive properties of tall and apparently vulnerable towers and to design fortifications offering the minimum of a target to an enemy; yet the Mortella Point action clearly showed that in certain circumstances well-built gun-towers had an important role. In putting forward his proposal for a chain of such towers on the Kent and Sussex coast, Captain Ford was no doubt articulating ideas current among his military colleagues. When the English towers came to be built, their name was derived from the Mortella Point tower.

The reasoning was simple: the Mortella tower had successfully driven off two heavily-armed warships. British towers would be able to do the same and would be even more devastating against lightly-built and largely unarmed invasion barges. A chain of towers within gun-shot of each other would be mutually protective and would offer formidable defence against a French invasion force. Even if the French were able to land artillery and subdue a number of towers, the resultant delay would provide vital time for the main British forces to concentrate and to contain the enemy.

Ford's scheme, submitted to his senior officer Brigadier General William Twiss, commanding officer for the southern district, was passed to the Master of Ordnance and eventually to the Committee of Royal Engineers tasked to evaluate such schemes. The tactical purpose of the Martello Towers was described by the Quartermaster General's Department in their plans of 1803:

The advantage proposed by these towers is to keep possession of the defences to the annoyance of the enemy during the whole operation of his landing, and the probable prevention of his disembarking stores; and either to oblige his bringing artillery against them when he has landed or leaving us in possession of the bay or anchorage which they protect - would enable us to intercept all supplies which he might endeavour to follow the Armament.

Opinion was generally in favour of the idea but differed sharply on the number and design of the towers. Ford's square tower was abandoned in favour of a round one and for reasons of cost, many favoured using the towers to guard only the most vulnerable beaches, protect marshland sluices and to supplement existing fortifications.

Brigadier General Twiss wrote in 1804:

My first object was to apply the general Principles of Fortification which the Committee of Royal Engineers had approved to the defence of the exposed line of coast and it occurred to me that the simple tower of about 29 feet diameter, arched over, and having on the top one heavy gun assisted by carronades or swivels would, (except in five instances which are hereafter enumerated, and where towers for four guns are recommended) apply throughout, placing them each 5 or 600 yards of each other in the most advantageous landing places and extending their distances as circumstances might render admissible.

In May 1804 William Pitt replaced Addington as Prime Minister; Pitt was known to be interested in coastal defences and it is probably no coincidence that within a few months of his taking office, Twiss was sent to survey the coast between Beachy Head and Dover to select sites for a chain of towers.

Twiss submitted his report in early September, recommending 58 towers to protect vulnerable beaches, Rye Harbour and the Romney Marsh sluices. At Sandgate, Henry VIII's castle was to be modernised and re-equipped. Armed with this report, but faced with conflicting views on the design, spacing and even the need for such fortifications the Privy Council ordered a conference to be held at Rochester on 21 October 1804 to discuss the whole question of coastal defence. While this debate was in progress - and proving that the government could act with remarkable speed if necessary - Lt Col John Brown submitted a plan for a defensive canal from Hythe to the river Rother to isolate Romney Marsh from the high ground to the rear; a western extension from the River Brede to Cliff End was to cut off Pett Level and Winchelsea Beach.

Three substantial military advantages were seen for such a canal: it formed a physical barrier sundering the marshland from the rest of the country; it avoided the need to inundate the marshland with all the attendant damage to property, grazing land and livestock, and barges on it would provide rapid transport for troops. Brown's report went to the Commander-in-Chief on 18 September; eight days later Pitt authorised construction of the Royal Military Canal.

Red Dragon I.T. Ltd.

Red Dragon I.T. Ltd.